‘The Boy and the Heron’ Review: Miyazaki’s Latest Is a Feast for the Eyes

Studio Ghibli’s The Boy and the Heron was once announced to be animation genius Hayao Miyazaki’s latest feature film, as the 82-year-old co-founder of the studio was looking to retire after a glorious career filled with movies like Spirited Away or My Neighbor Totoro. Most filmmakers can only dream of achieving something half as good. But Miyazaki fans were equally delighted and surprised to find out earlier this fall, in the lead-up to The Boy and the Heron‘s debut at Toronto, that he was nowhere near retirement. While that may have seemed unexpected going into his latest film, coming out of it, it makes perfect sense.

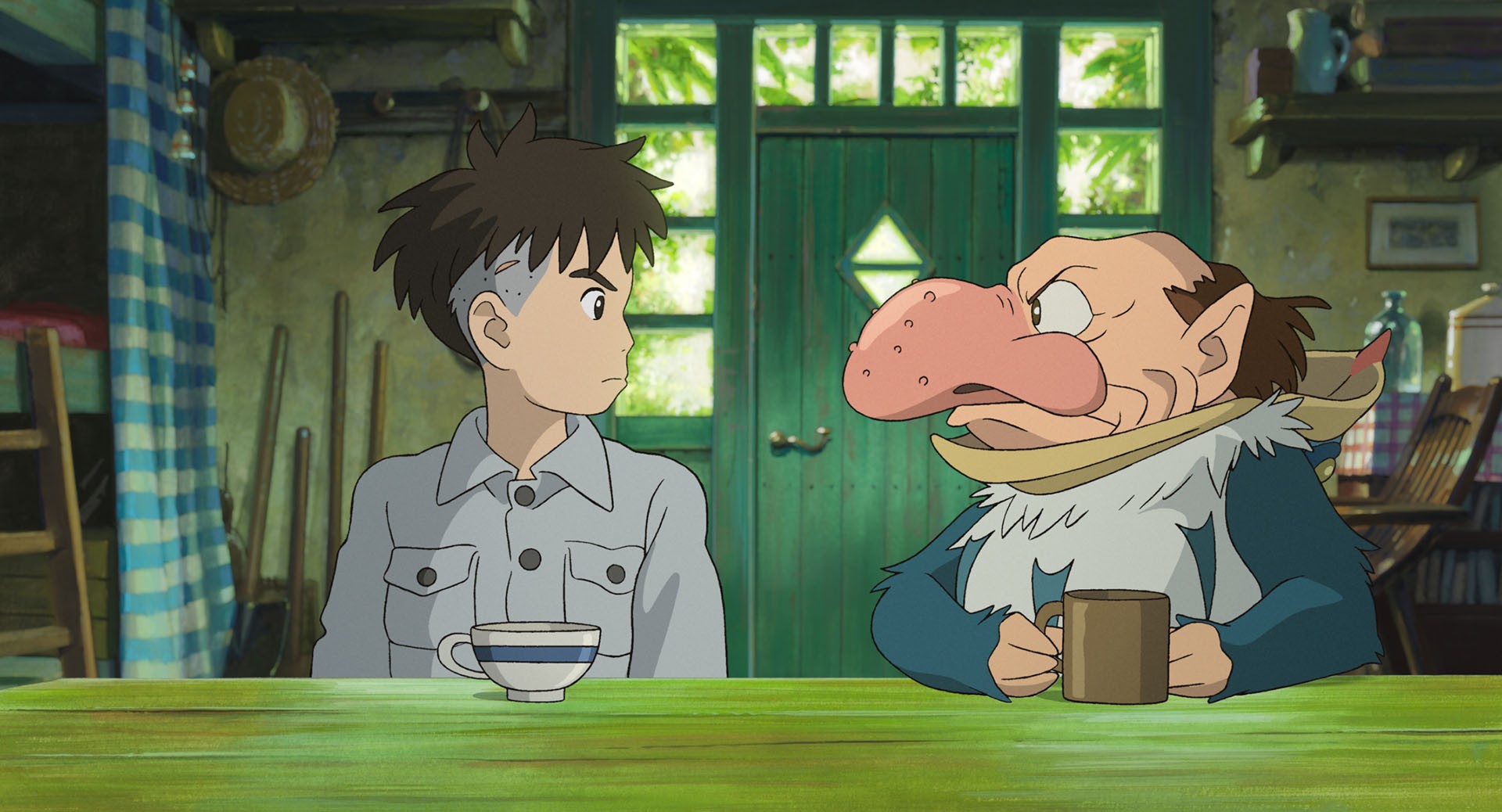

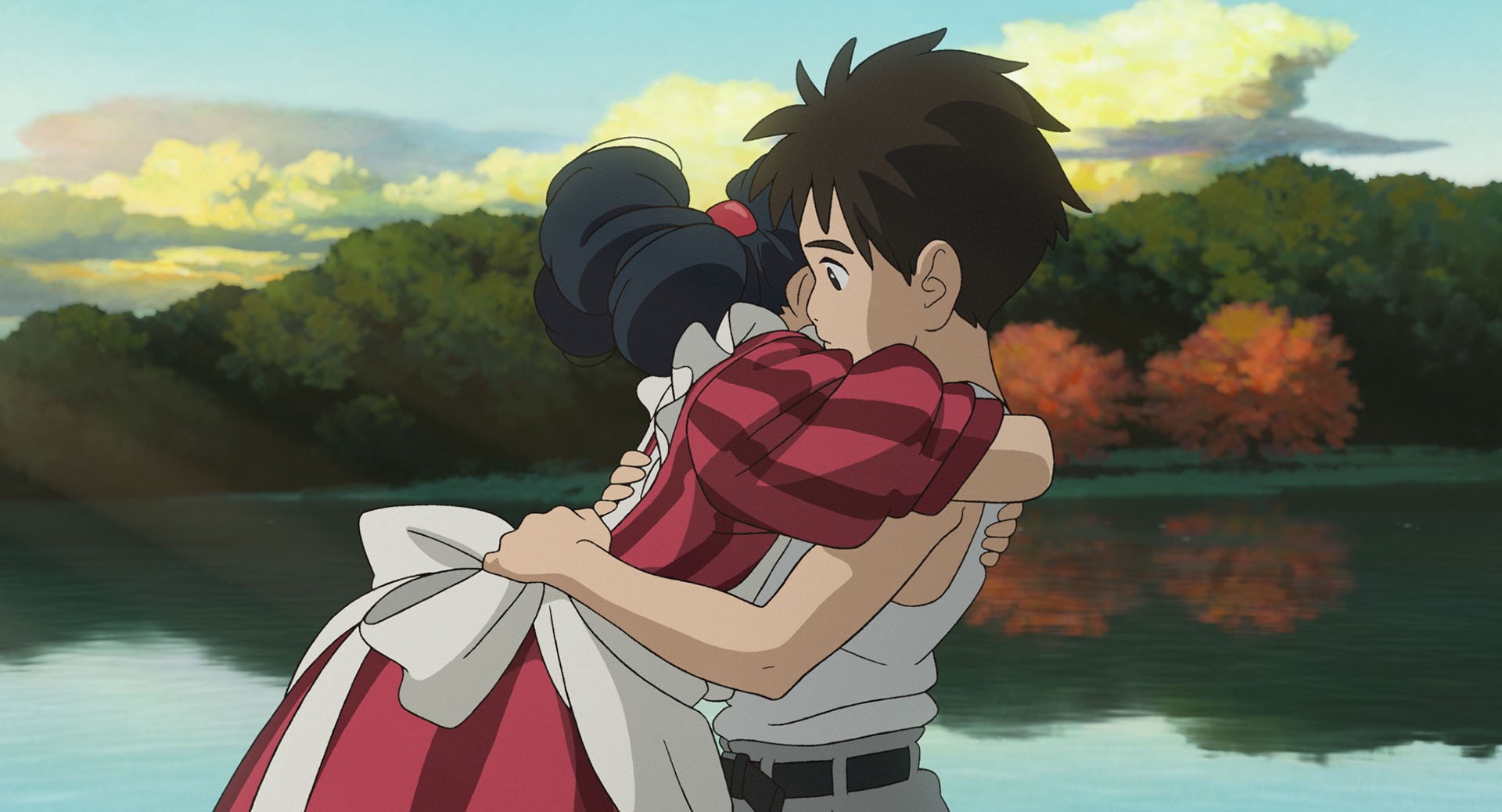

The Boy and the Heron is an absolute feast for the eyes, featuring hand-drawn animation with such vivid colors they feel like they have a life of their own, and characters so perfectly penciled to life you can pull up an accurate bio for them just by looking at how they were designed. But more than anything, the film is filled with such raw imagination that it feels like Miyazaki poured his entire soul into it, and in the meantime, he realized he had so much more to give to the world.

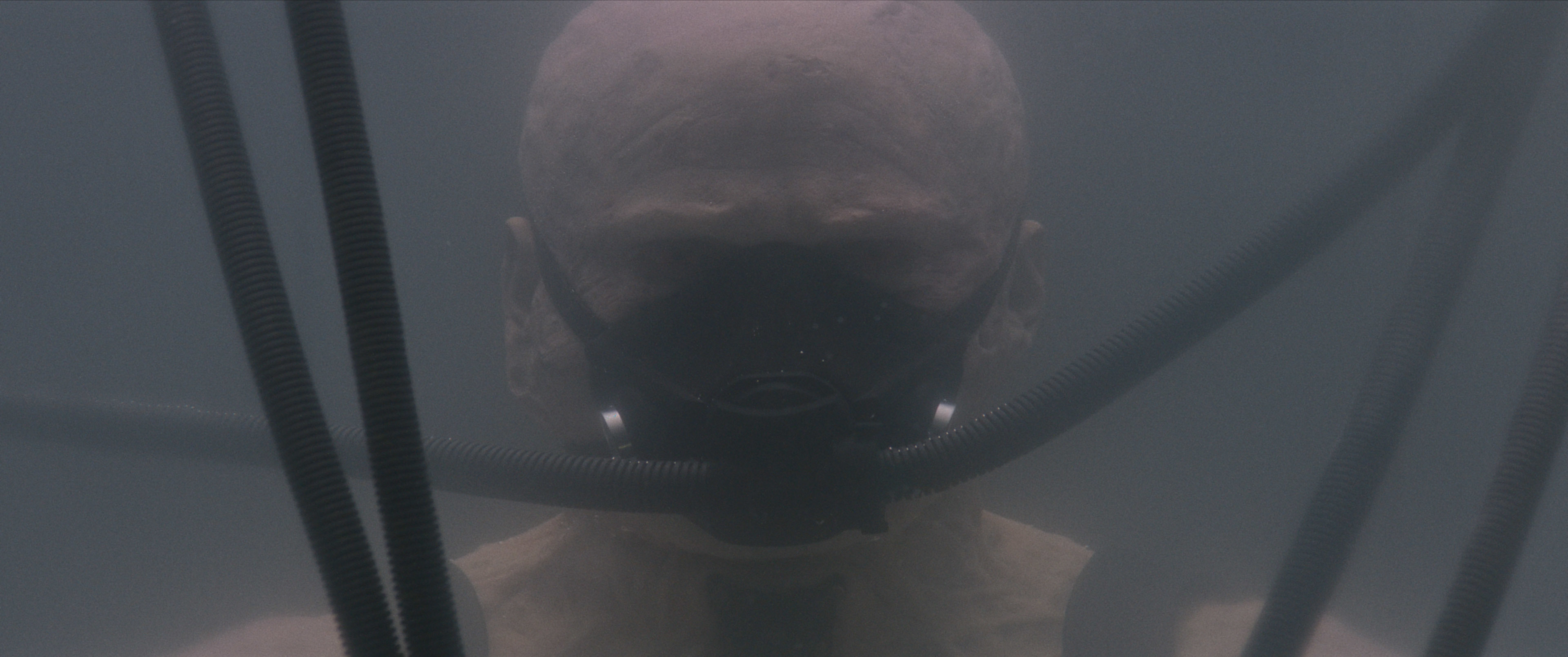

This is not a conventional story by any means, which is also what makes it so great. It’s the type of film that will require long conversations after the credits are over, as it isn’t easy to provide us with answers to our questions. Some of the mysteries are left completely up in the air, as Miyazaki isn’t afraid to have some loose ends while wrapping up the core storyline. Others are resolved with an even greater mystery that may or may not have real-world allegories for us to interpret.

In a film environment with so many predictable storylines and the absolute terror of not tying up every single thing set up along the journey, The Boy and the Heron sticks out as being brave enough to trust the audience will be able to understand that there are some things are best left unexplained. It’s the difference between a filmmaker telling a story for an audience and telling one that comes directly from the heart, feeling the need to put it out in the world more than the necessity of having the world’s approval. The sign of a true artist.

It is that unpredictability that also creates a massive armor around the actual story of the film — and any Studio Ghibli project, for that matter. Miyazaki famously released the film in Japan earlier this year without any trailers or advanced looks. For that reason, discussing any specific plot points may be sensitive to some readers. If you wish to watch the film without knowing anything else about it, this is your cue to exit. But for those of you who won’t mind reading the logline before going into it, allow me to explain the basic concept behind it.

The story follows the young boy Mahito as he comes to terms with the recent passing of his mother, while his father (in one of the film’s biggest unresolved mysteries) moves on with his life and impregnates his wife’s sister, who will now be Mahito’s new mother. It is the journey of letting go of the image he had of his mother and accepting that life is more complex and nonsensical than any eleven-year-old boy can fathom that drives Mahito through a series of fantasy realms after meeting a slightly annoying but morbidly interesting heron.

In a fitting turn for the 82-year-old filmmaker, The Boy and the Heron touches on themes of legacy and the cycle of life. How when one life ends, another begins, and how coming to terms with the death of your own mother is no different than accepting your own mortality, which is as frightening to do for an eleven-year-old as it is for an old man two steps away from his grave. Coming from a country still trying to reconcile with its mushroom-shaped wounds from 80 years ago, there was no other time for Miyazaki to set the story than World War II, which itself provides a ton of context for the themes that the story explores elsewhere.

The film is so visually expressive (and stunning, have I mentioned that?) that you can even take out the subtitles and you might have a similar sense of what is going on in the story than when you can understand the dialogue. The key asset here is Miyazaki’s imagination, on full display once the story kicks into high gear — which it also takes its time to do, with Miyazaki using the full power of a two-hour runtime to properly set up the stakes and carefully move around the players until they are ready to enter a fantasy world where the rules that govern our world and also our stories are no longer applicable. And it’s all for the best.

At its core, it’s a film about the artist as much as it is about the world he lives in. It explores the meaning of life as much as it explores the meaning of art (are those two even different conversations?). Early on in the film, you might have a sense that this is going to be another run-of-the-mill story about a boy who can’t really get over his mom’s death and finds an escape in a magical creature that shows him there’s more to life than death. But that is not what is going on. With The Boy and the Heron, Miyazaki is on his feet asking us not to let his life’s work go to waste, for someone else to not let this genre and these stories die. He’s looking for an heir while also second-guessing himself, thinking “Will someone else even think this is worth the trouble in such a messed-up world?”

The Boy and the Heron is currently available in a few markets around the world and will open in the US on December 8.

Miguel Fernández is a Spanish student that has movies as his second passion in life. His favorite movie of all time is The Lord of the Rings, but he is also a huge Star Wars fan. However, fantasy movies are not his only cup of tea, as authors like Scorsese, Fincher, Kubrick or Hitchcock have been an obsession for him since he started to understand the language of filmmaking. He is that guy who will watch a black and white movie, just because it is in black and white.