‘Oppenheimer’ Review: Christopher Nolan’s Diluted Biopic Could Have Been Masterful

Throughout film history, there are excellent examples of how studios nearly ruined movies that are now considered classics by giving absurd notes or asking for ridiculous changes. We like to look back at those examples and use them as the definitive argument of why studio executives should shut their mouths and let the artists do their thing; this is an art form that turned into a business, after all. Look no further than James Cameron’s filmography, most of it populated by the Titanic director shutting doors on 20th Century Fox executives’ faces when they tried to cut down the $2.8B-grosser Avatar. And yet, Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer is one of those examples where anyone from Universal asking Nolan to refocus the narrative and trim down its otherwise nail-biting runtime would have propelled the movie to its full potential.

When Oppenheimer works, it is cinema at its finest. Ask any other director in Hollywood to make a biopic about a theoretical physicist deliberating the moral grounds of his own research as engaging, thrilling, and full of tension, and also make more money opening weekend than Tom Cruise jumping off a cliff. No, really; ask them. Ask any studio. Nobody else would be able to achieve those staggering results, and the movie is an excellent example of why Nolan is one of the best directors today. But nobody’s ever said he’s one of the best screenwriters of our time, and that’s where the movie starts to become a black hole generated by Nolan’s own pride. He’s too attached to what he wrote on the page to cut down plotlines that ultimately hurt the movie more than they add layers to the complexity of J Robert Oppenheimer (Cillian Murphy).

Case in point, Robert Downey Jr. The Iron Man actor reinvents himself with his best performance by far since his Tropic Thunder days, one that sends a clear message: “I do not want to be remembered just as Iron Man.” His work on Oppenheimer should put a definitive end to any speculation about his return to the Marvel Universe and will be used as self-promotion for most of our great directors to see and think “Yes, I want to work with that guy”. Don’t be surprised if David Fincher or Steven Spielberg come knocking on his door soon; Adam McKay already has, and there are bigger names to come. And yet, there’s an argument to be made that the movie would have benefitted from limiting his contribution to the story to just a handful of scenes.

L to R: Robert Downey Jr is Lewis Strauss and Cillian Murphy is J. Robert Oppenheimer in OPPENHEIMER, written, produced, and directed by Christopher Nolan.

In his life, J Robert Oppenheimer had to deal with four major battles. He had a wife (Kitty, a sublime Emily Blunt, who is as sidelined in the movie as she was in Oppenheimer’s life) and two children to take care of, as well as an affair with Jean Tatlock (an electrifying as usual Florence Pugh), who adds more to the story than being “just a mistress”. He had to fight physicists as part of her job, from the moment he brought Quantum Mechanics to the United States and started teaching it in colleges, to the day-to-day debates during the Manhattan Project (namely, with Benny Safdie‘s Edward Teller).

Said project was part of the Americans’ World War II efforts, so he also had to deal with the military (represented in the film by an unhinged Matt Damon), and because of his past with connections to the Communist Party (including Jean Tatlock herself), there are also political pressures on him, both during and after the war — that’s where Downey Jr.’s Lewis Strauss, as well as an investigating committee led by a killer Jason Clarke, come in. All of those seemingly-disconnected threads converge in Los Álamos, where the Manhattan Project established its main base of operations and detonated the first atomic bomb during the Trinity tests in July 1945, just mere weeks before the Americans dropped two of them on Japanese cities. And the world would never be the same.

Nolan’s script does a good enough job at establishing all of those storylines and the importance of each one of them, but ultimately betrays the ranking it succeeded at establishing when it prioritizes the subplot about Oppenheimer’s investigation to the Communist Party, arguably the least interesting of all four of them. Obviously, Nolan wanted this to be a biopic, but in the first 20 minutes, when he rushed through most of Oppenheimer’s pre-Berkeley days with such fast-paced editing by Jennifer Lame that one would have thought we were watching an action movie just based on the rhythm, the director lets us know that he wants to tell the story of the creation of the atomic bomb. During the film’s second act, the story is finally allowed some breathing time, even if Lame still wants to rush us to the next scene to keep that rhythm and double down on the tension (Ludwig Göransson’s magnificent score allowed the editing to feel twice as powerful).

All of it is used as build-up to the Trinity tests sequence, and all of it works, for the most part. There are interesting conflicts along the way, all of them anchored by a nuanced performance by Cillian Murphy. This is also where the writing starts to fumble — Nolan has made it very clear during the press tour that he considers Oppenheimer “the most important man who ever lived”, and the weight of his work is absolutely not to be taken lightly. As such, the trailers painted the physicist as a figure who had to wrestle with the most important decision in the history of mankind — whether to pursue the power to destroy ourselves.

The answer is not as clear as day, and Oppenheimer finds himself in the middle of a heated debate between politicians and soldiers who want to put an end to the war and establish the United States as the biggest, baddest country on Earth, and the group of scientists who can make that happen but are unsure if it will be worth the consequences. But what does Oppenheimer think? Well, Nolan won’t really tell us, which is why Murphy’s performance feels halfway at times.

L to R: Emily Blunt is Kitty Oppenheimer and Cillian Murphy is J. Robert Oppenheimer in OPPENHEIMER, written, produced, and directed by Christopher Nolan.

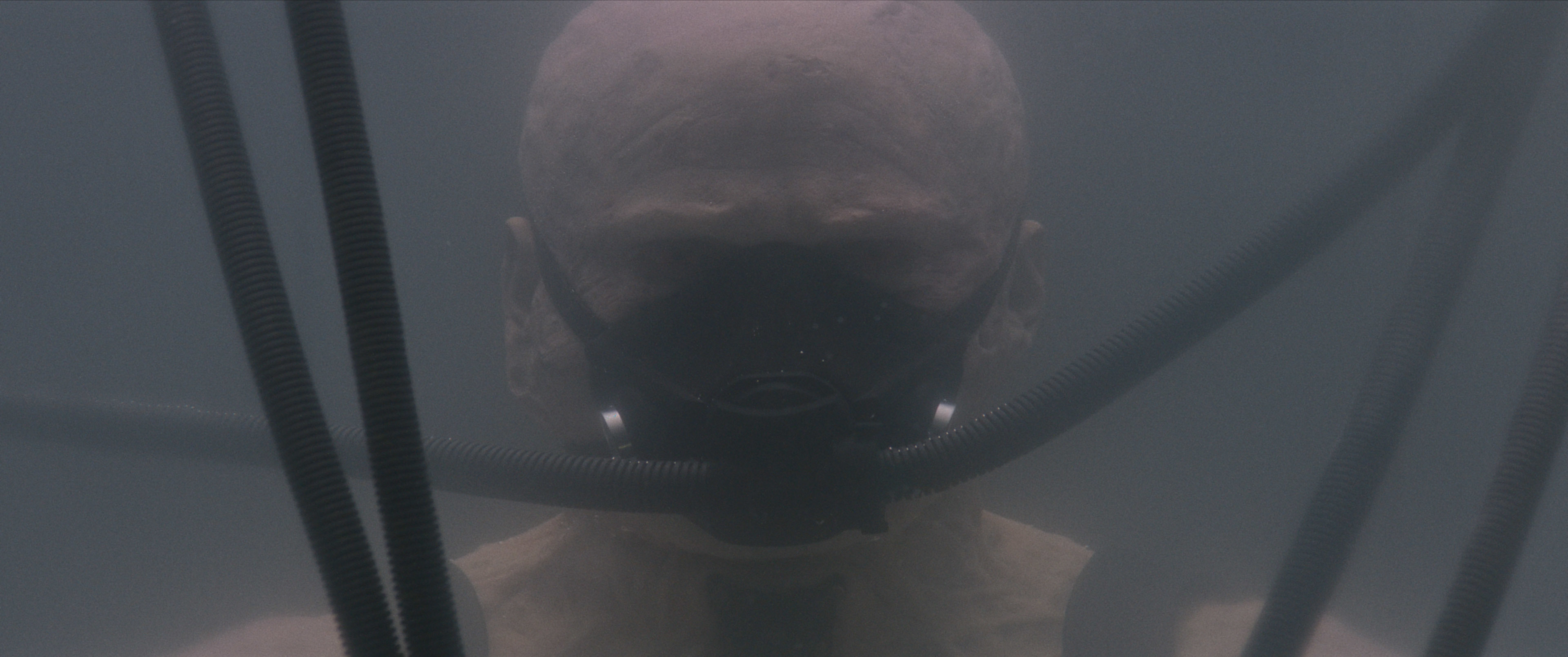

Instead, Nolan chooses to structure the film in a way that puts the Trinity tests, the culmination of Oppenheimer’s work, as the end of the second act, and leaves the third act to what happened later — the post-war investigation into how the Russians also acquired the secrets of the Manhattan Project. The beginning of the Cold War. And yes, the story of a man who arguably led his own country to definitive victory and also gave it the definitive power in the world but was later betrayed by that very country (one that so adamantly pursues political freedom, freedom of speech and freedom of thought), because of the ideas that some of his peers had, and yes, even a few that he agreed with, is a story interesting enough to tell. But in the context of Oppenheimer’s life, it is but a shadow of his biggest work and the struggle that took over every cell of his body — is this bomb worth creating?

And it’s not like that question is not repeated throughout the course of the film; in fact, it is during those moments where it shines the brightest; when it’s about different people in different rooms sharing their various perspectives on the matter. But what does Robert think? Well, that is exactly what everyone is asking, and while the reality is that he probably shifted his own thoughts throughout the years working on the project (eventually leading to his famous “I am become death, the destroyer of worlds”, a line that is first introduced in the movie in a now-controversial scene), he never really says in the movie.

Cillian Murphy is J. Robert Oppenheimer in OPPENHEIMER, written, produced, and directed by Christopher Nolan.

The majority of the script is written in the first person, symbolized in the movie as the scenes in color — this is not something that is immediate for someone who hasn’t been following the marketing campaign, but Nolan does a good enough job signaling that the scenes in black and white are more objective, while the rest are clearly subjective. As such, Nolan decided to give us the power of the detonator — he won’t tell us what Oppenheimer is thinking, because he gives the audience the power of that decision after weighing all points of view.

Much like Oppenheimer’s decision, making a definitive judgment on the movie is almost impossible. There is so much to consider on both sides of the spectrum, and in the end, where I’ve landed is that it’s a good movie, but it could have been great. There is an arguably much better cut of Oppenheimer, at around 2h 20 min, lying in the quantum space had a studio executive asked Nolan to remove most of the fluff from the investigation into his communist ties. It is true that this is a biopic, but telling the story of a man in just 2-3 hours means prioritizing some aspects over others. And the heart of the film is clearly the days of the Manhattan Project and his experience in Los Álamos, which Nolan forgot during part of the story.

Even in the current runtime, there are aspects of the atomic bomb history that weren’t explored; going no further, the international community, devastated by the sheer existence of the atomic bomb, decided to form the United Nations, a pivotal organization of our world that is simply mentioned by name once in the film. Physicists around the world shared that sentiment and decided to form an alliance to do fundamental research with the only purpose of peace. In the 1950s, CERN was born, the biggest scientific facility in the world, which not only is still in operation, but it’s where the World Wide Web was invented in the late 1980s. (I have many notes on how science is presented throughout the film, but I’ll keep those to myself as I don’t really think they are valid criticisms of the filmmaking displayed.)

Oppenheimer is currently playing in theaters worldwide.

Miguel Fernández is a Spanish student that has movies as his second passion in life. His favorite movie of all time is The Lord of the Rings, but he is also a huge Star Wars fan. However, fantasy movies are not his only cup of tea, as authors like Scorsese, Fincher, Kubrick or Hitchcock have been an obsession for him since he started to understand the language of filmmaking. He is that guy who will watch a black and white movie, just because it is in black and white.